Author Q&A

Q. How did the idea for this book come to you? Why did you feel a need to write Eliza Scidmore’s story?

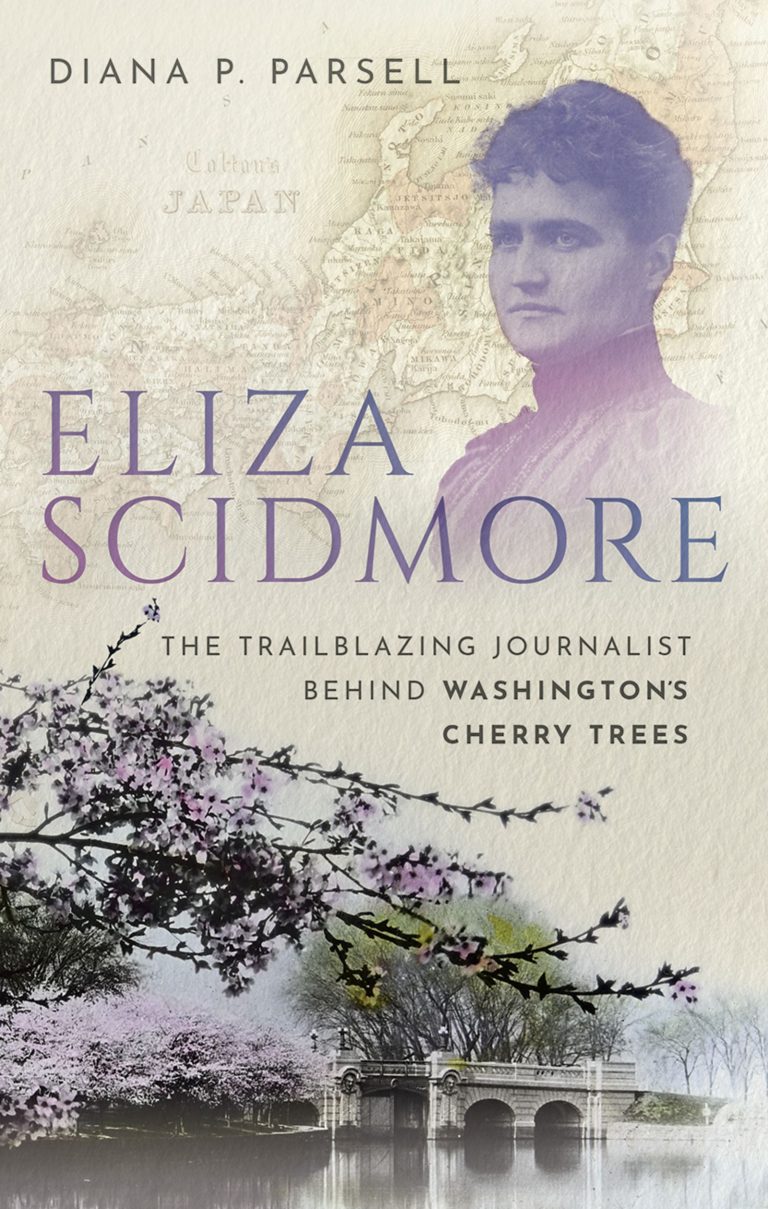

A. I discovered Eliza Scidmore by chance years ago in a paperback book I bought while living and working in Indonesia. It was a modern reprint of an 1897 travel book, Java, the Garden of the East. I found it so engaging I did a quick internet research to find out more about the author. What a surprise to learn that E. R. Scidmore was an American woman, one who traveled widely in the Far East, published seven books, and was National Geographic’s first female board member and photographer. Most astonishing was her key role in giving Washington its now-famous cherry blossoms. I had lived in the D.C. area over three decades and went every year to see those trees. How had I never heard of this woman?

As a longtime journalist, I knew it was rare that you stumbled across a truly original subject. But this seemed the real thing: a remarkable woman’s story never fully told. Having “discovered” Scidmore, I came to feel almost an obligation to write her back into history, to give her the credit she was due. Thus began the decade-long project that became my first book.

Q. Can you talk a little about the research process. How did you go about it, and what findings surprised you the most?

A. Living in suburban Washington gave me ready access to the Library of Congress, a remarkable resource for any author. Not trained as a historian or academic, I had no idea how to go about researching a biography, so I started with Scidmore’s books and went from there. At first, I found little about her. By following one clue after another, however, I eventually uncovered relevant material at about two dozen archives and libraries, much of it “hidden in plain sight” for years in databases, letters, image collections, public records, and other sources. Historical newspapers—once I cracked the code of Scidmore’s pen name—were especially helpful because the datelines enabled me to chronicle her travels. Seasoned biographers stress the importance of “walking in the footsteps” of your subject, so my research included self-funded trips to Japan and Alaska, as both places were critical in her story.

Several findings were especially notable. First, Scidmore’s remarkable 40-year career as a journalist and travel writer, starting as a newspaper correspondent in Gilded Age Washington. Also, her pathbreaking reporting from China. Some scholars have written that she was one of a handful of Western writer-travelers who “opened” China to mass tourism in the late 19th century, yet this aspect of her life is hardly known. Finally, I uncovered new evidence showing she was not only the earliest visionary of cherry blossoms in Washington but actually mediated the offer of several thousand cherry trees from Japan in 1912. Turns out, we owe her far more than people ever realized when it comes to the spectacle that draws more than a million people to the nation’s capital every spring.

Q. What was tourism like in Scidmore’s day. Who was traveling, by what means, and where to?

A. In the post-Civil War era when Scidmore took up journalism, most Americans spent their lives in their own backyards. Tours of Europe, and increasingly to “exotic” places like the Far East, were fashionable among the well-to-do; leisure travel was a luxury. That began to change in the late-19th century, as rising incomes, transportation advances and social aspirations fueled a wave of middle-class tourism. The American West, with its dramatic scenery and colorful frontier life, became a favored destination. Alaska’s cruise industry was born during that period, when a round trip cost about the equivalent of a government clerk’s monthly salary. Round-the-world trips, popularized by people such as Nellie Bly, captured the public’s imagination.

In her published accounts, Scidmore describes traveling by train, carriage, ship, stagecoach; by jinrikisha, sedan chair, and wooden cart. Most larger cities in Asia had hotels that catered to Westerners, but she also ventured to places off the beaten track where conditions were more challenging. She always traveled with certain advantages as a white, well-educated American woman and the sister of a U.S. diplomatic official. Yet her keen attention to local geography and native cultures gave readers a sense of what today we would call “authentic” experiences. I’m in awe of her stamina and the sheer distances she covered. She traveled frequently between America and Asia at a time when an ocean crossing could take three weeks.

Q. You write that Scidmore was uniquely positioned to push the idea of Japanese cherry trees along the Potomac in Washington. How so, and what made her so obsessive about the idea?

A. Scidmore approached the world with an aesthetic eye. Traditional Japanese culture fascinated her in part for its refinement and beauty in the rituals of everyday life. She admired Japanese respect for nature, manifested in a love of plants and gardens. She called flowering cherry trees “the most beautiful thing in the world” and couldn’t understand why they had never caught on in Western cities and parks. Her determination to see it happen in Washington, despite hurdles along the way, reflects her dogged personality. Enlisting the support of First Lady Helen Taft as a partner came about from her talent for seizing opportunity.

I grew convinced that Scidmore’s devotion to her idea grew in part from her deep affection for her adopted city of Washington. She grew up there, and as a young journalist she reported on the city’s gradual beautification and the creation of Potomac Park on former mud flats near the Washington Monument. Having felt the transcendent joy of walking under cherry blossoms in Japan, she wanted to recreate that experience in the nation’s capital, where springtime tourism was taking off. She saw the new park along the river as an ideal spot.

Q. Do you think Scidmore left a legacy beyond the cherry trees?

A. Beyond the cherry trees, I see Scidmore’s legacy rooted heavily in her intrepid travels and journalistic work that made her an important agent of early cross-cultural understanding. Through her words and observations, she brought distant places alive for Americans in an era before photography and social media dramatically shrank our experience of the world.

By her mid-20s, she had visited more places than most people would see in a lifetime; by the end of the 19th century, her travels were so legendary she was introduced at a meeting in London as “Miss Scidmore, of everywhere.” At a time when the box camera was still a novelty, reviewers of her half-dozen books commented regularly on the “Kodak” vividness of her writing.

Q. You show that Scidmore was something of a celebrity in her day. Why, given her remarkable achievements, did she essentially fall through the cracks of history for more than a century?

A. I puzzled from the start of my research why Eliza Scidmore eluded attention for so long. When I posed the question to women’s studies experts at the Library of Congress, they explained that a paucity of records is a common challenge in writing women’s history. For centuries, women’s lives were not deemed worthy of documenting. A lot of women’s history, they noted, is buried in the papers of the men in their lives. But Scidmore never married, and her own papers were destroyed by a relative after her death.

Moreover, she spent her final years in Europe. After her death in 1928, her ashes were deposited at a cemetery in Yokohama alongside the remains of her mother and her brother, who spent most of his U.S. consular career in Japan. So, while the Japanese have paid tribute to Scidmore over the years as an early “friend of Japan,” there was no one to champion her legacy in her native America. It was only when I uncovered many of her previously overlooked articles and letters that I found the kind of primary source material that’s essential for a biography.

(for Oxford University Press, use code AAFLYG6 for 30% discount)